Every System is a Log: Avoiding coordination in distributed applications

Stephan Ewen, Jack Kleeman, Giselle van Dongen

Building resilient distributed applications remains a tough challenge.

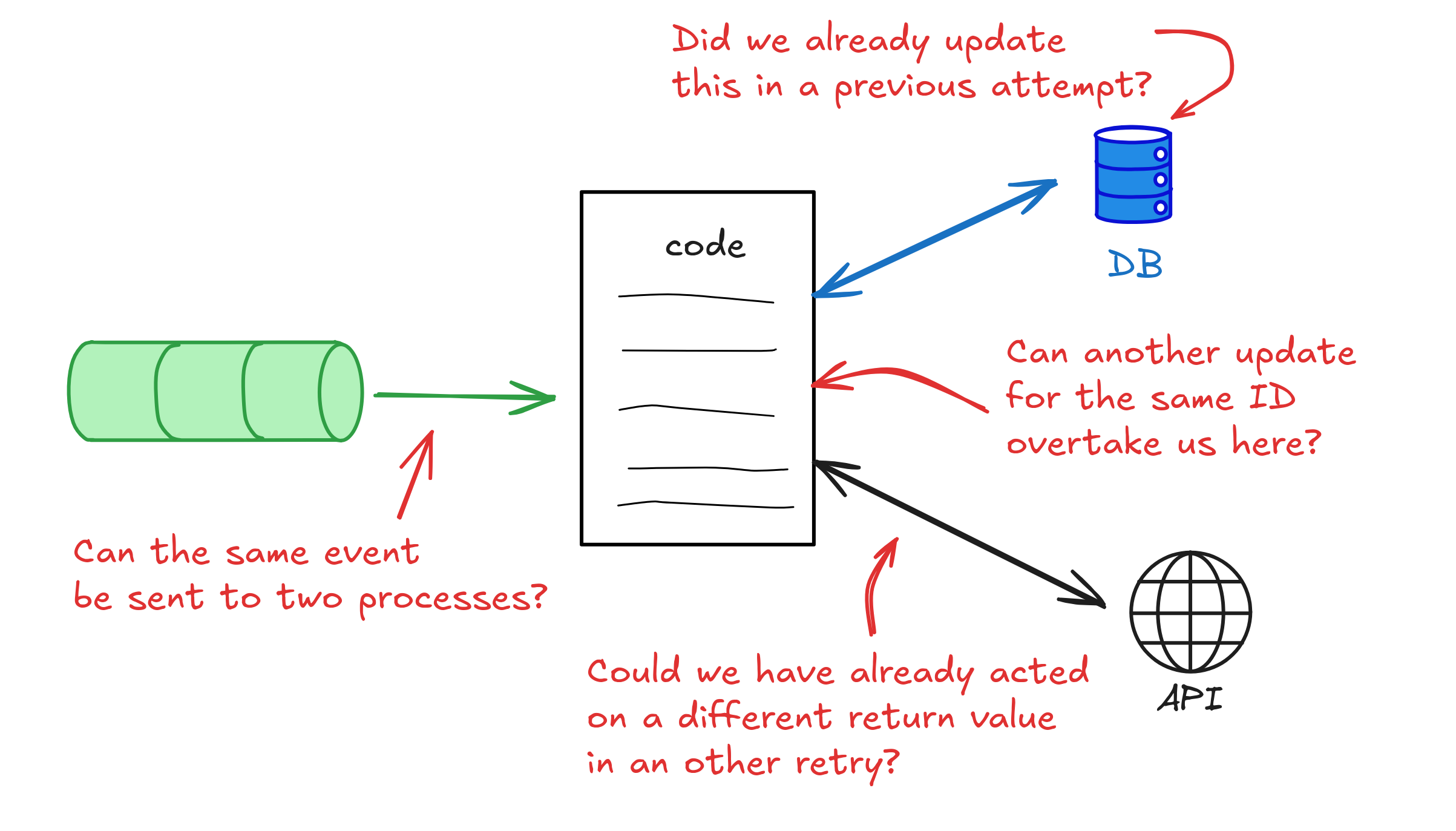

It should be possible to focus almost entirely on the business logic and the complexity inherent to the domain. Instead, you need to review line-by-line and check: “what if the service crashes here?”, “what if the API we call here is temporarily unavailable”, “what if a concurrent invocation overtakes this one here”, or “what if this process becomes a zombie while executing this function, how do I prevent it from corrupting the state?”.

As a result, you spend a huge amount of time worrying about failover strategies, retries, race conditions, locking/fencing, ordering of operations, order visibility of changes, decoupling availability, etc. They add queues, key-value stores, locking services, schedulers, workflow orchestrators and they try to get them all to play nice together. And the hard truth is, many applications don’t get it right and are not correct under failures or even under load.

How can we radically simplify this? In this article, we walk through a core idea that addresses many of these issues, by avoiding distributed coordination. Much of this goes back to learnings from when we built Apache Flink.

Every System is a Log

Let’s start with an observation about distributed applications and infrastructure: Every System is a log.

-

Message queues are logs: Apache Kafka, Pulsar, Meta’s Scribe are distributed implementations of the log abstraction. Message brokers (e.g., RabbitMQ, SQS) internally replicate messages through logs.

-

Databases (and K/V stores) are logs: changes go to the write-ahead-log first, then get materialized into the tables. The database community has the famous saying “The log is the database; everything else is cache (or materialized views)” - often attributed to Pat Helland. The idea of “Turning the Database Inside Out” starts with a log.

-

Distributed locking- and leader election services (like ZooKeeper, Etcd, ...) are consensus logs at their core. Consensus algorithms, like Raft, inherently model log replication.

-

Persistent state machines materialize logs of their state transitions.

When you build an application or microservice that interacts, for example, with a database, a message queue, and a service API (backed by another database), you are orchestrating a handful of different logs in your business logic.

The broad applicability of thinking in logs has been described best in Jay Kreps' iconic blog post.

Applications need to orchestrate many logs

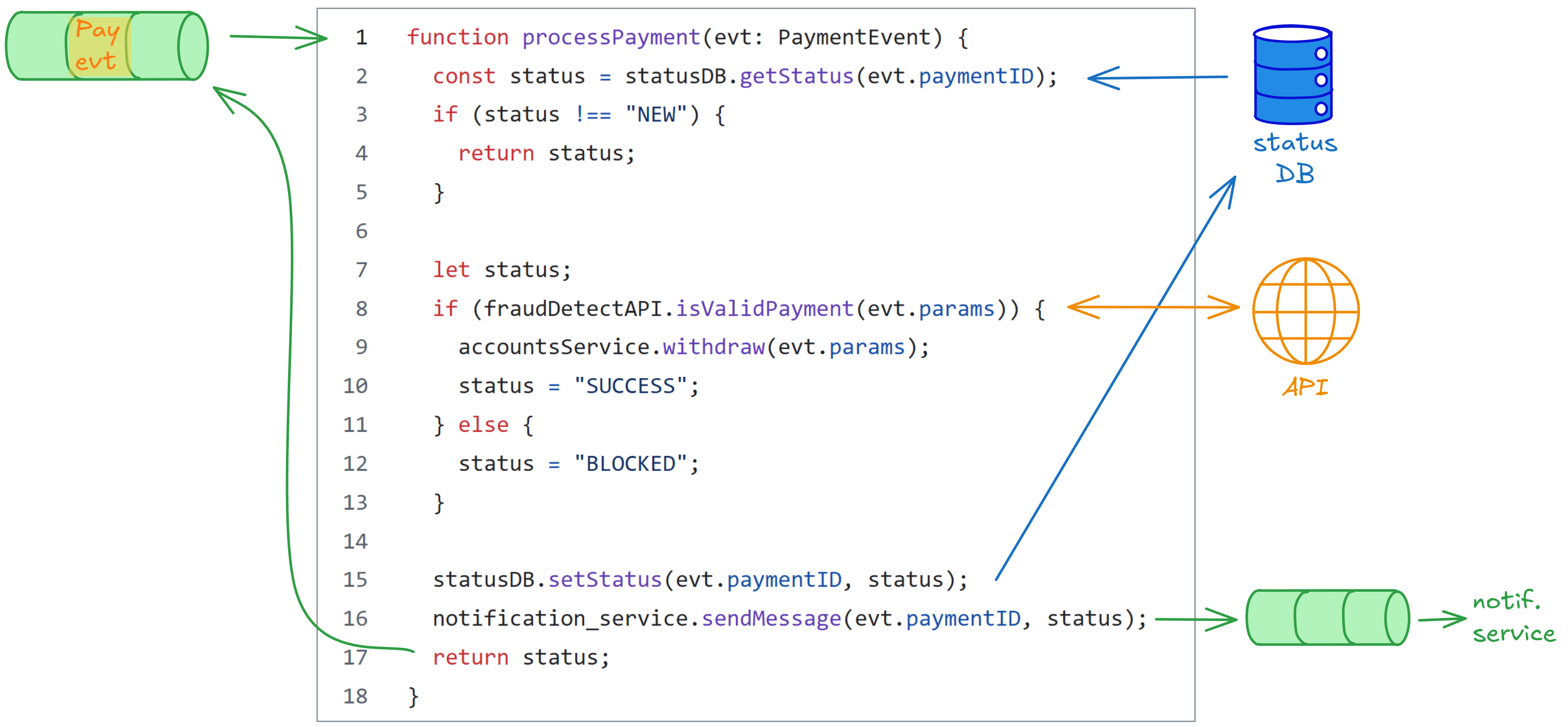

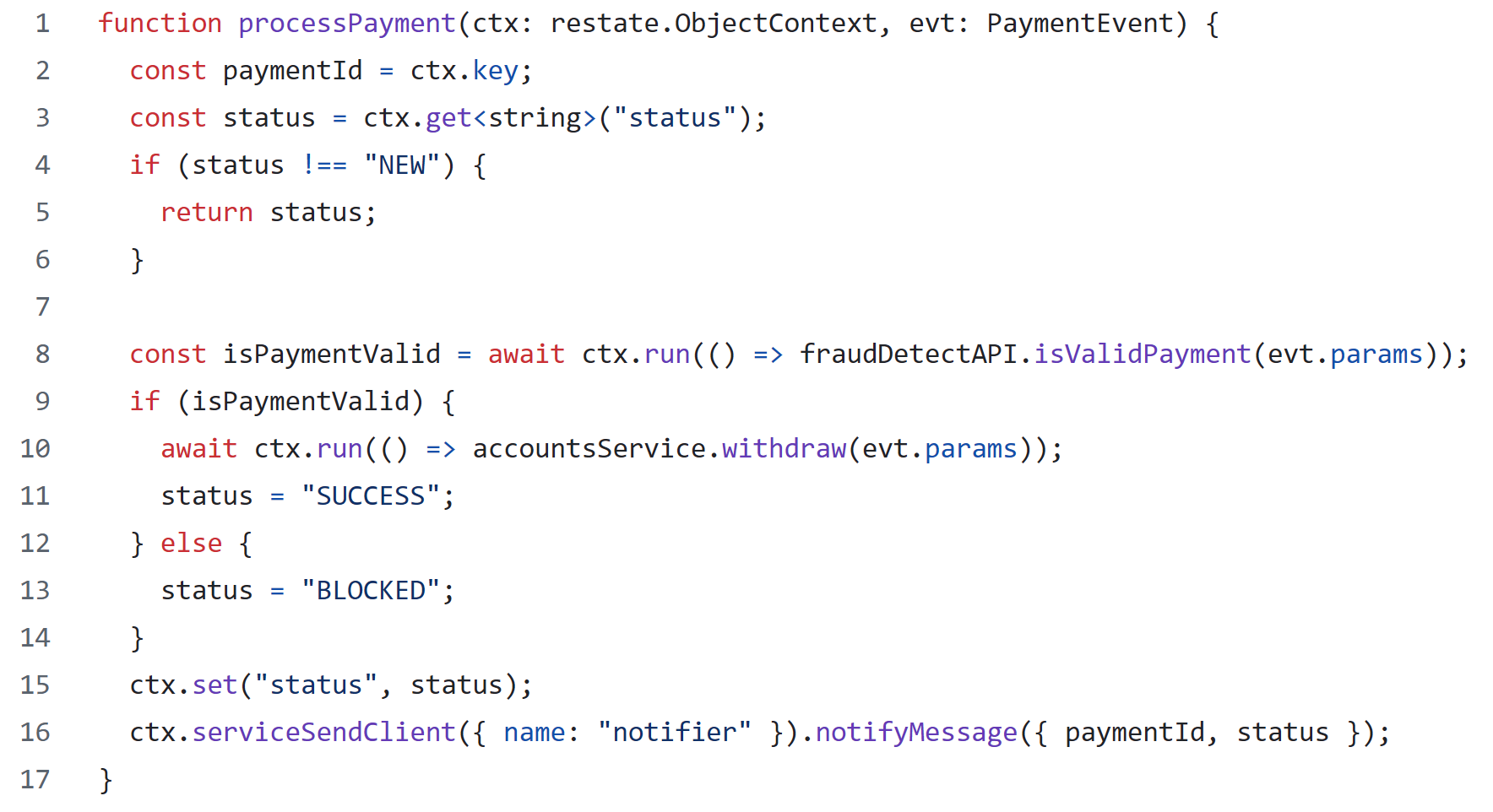

In this example, we want to implement a processPayment handler. The payment has an ID that identifies it. The handler is triggered from a queue (which also re-delivers the event if the handler fails or times out) and the processing involves checking a fraud detection model, updating account balance, storing the status, and sending a notification. There are other handlers that may handle the same payment ID, for example to cancel the payment, block it, unblock it, revert it.

You can probably spot some issues:

- Concurrent invocations (other handlers like “cancel”, or retries of the same event) can produce arbitrary results.

- A failure after line 15 means the next retry does nothing and we don’t send a notification.

- If the fraud model is not completely deterministic (or if it is updated between retries), we might assume a payment is valid, crash after line 9, the retry declares the payment not valid, and we are setting the status to BLOCKED despite the fact that we withdrew the money.

Nasty stuff! Let’s try to improve that.

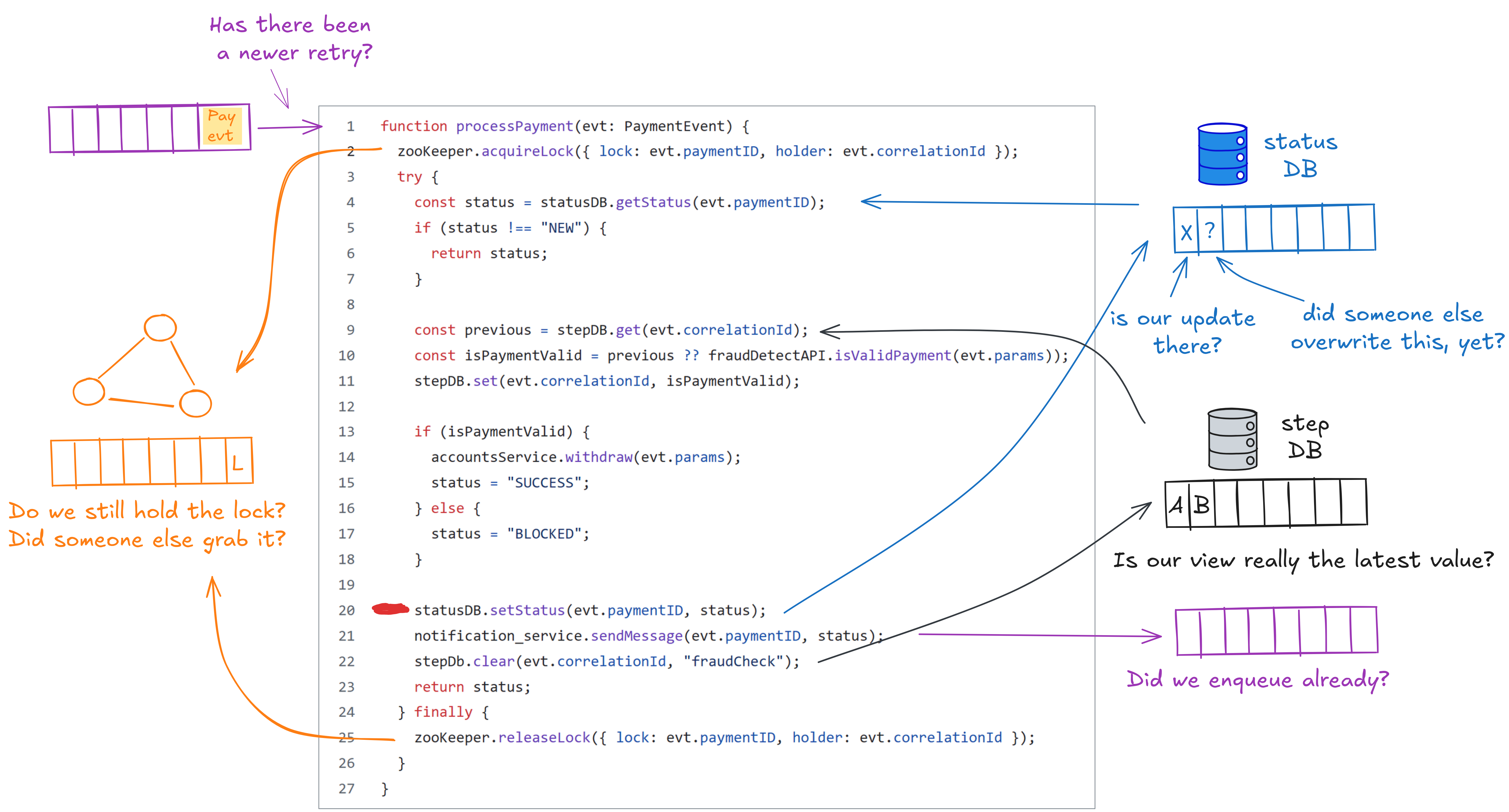

This second version of the code does some things better, but still has issues. One of them is around line 20, where we need to ensure that we are still the owner of the lock at the point in time where the database persists the update. That is really hard to do, because distributed lock release or re-entrance is never 100% correct, due to the impossibility of precise failure detection (is a process failed or just slow or is our network partitioned?), so locking generally requires an additional fencing mechanism. Martin Kleppmann has a great blog post about the rabbit hole of getting distributed locking right.

Why is it so hard to make this seemingly simple handler work reliably? Because our goal is to make consistent changes depending on the status of disparate systems, where each has its own view of the world, maintained in its separate log.

Distributed applications often need to implement a complex orchestration of all the systems they interact with, carefully designing all states and operations, to establish order and invariants that help them ensure correctness. This is the heart of much of the complexity in modern distributed applications.

What if it were all the same Log?

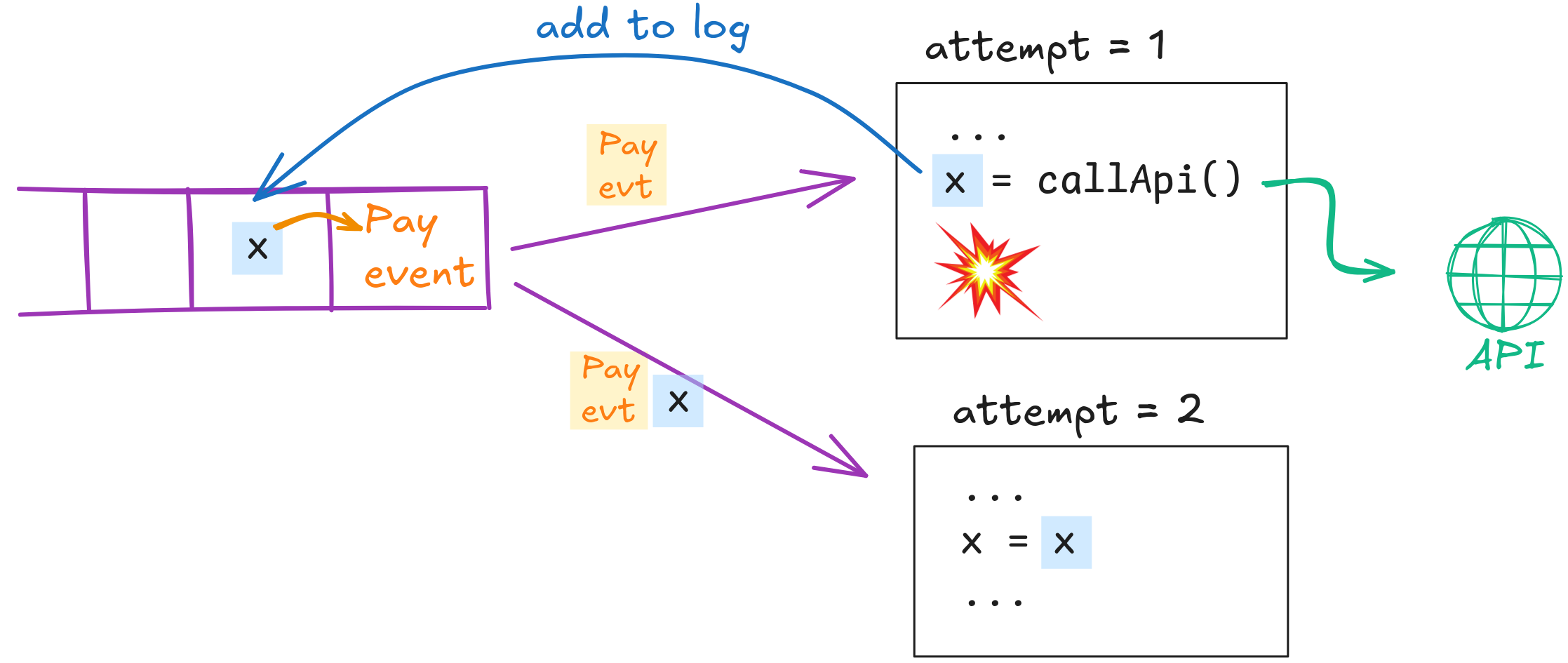

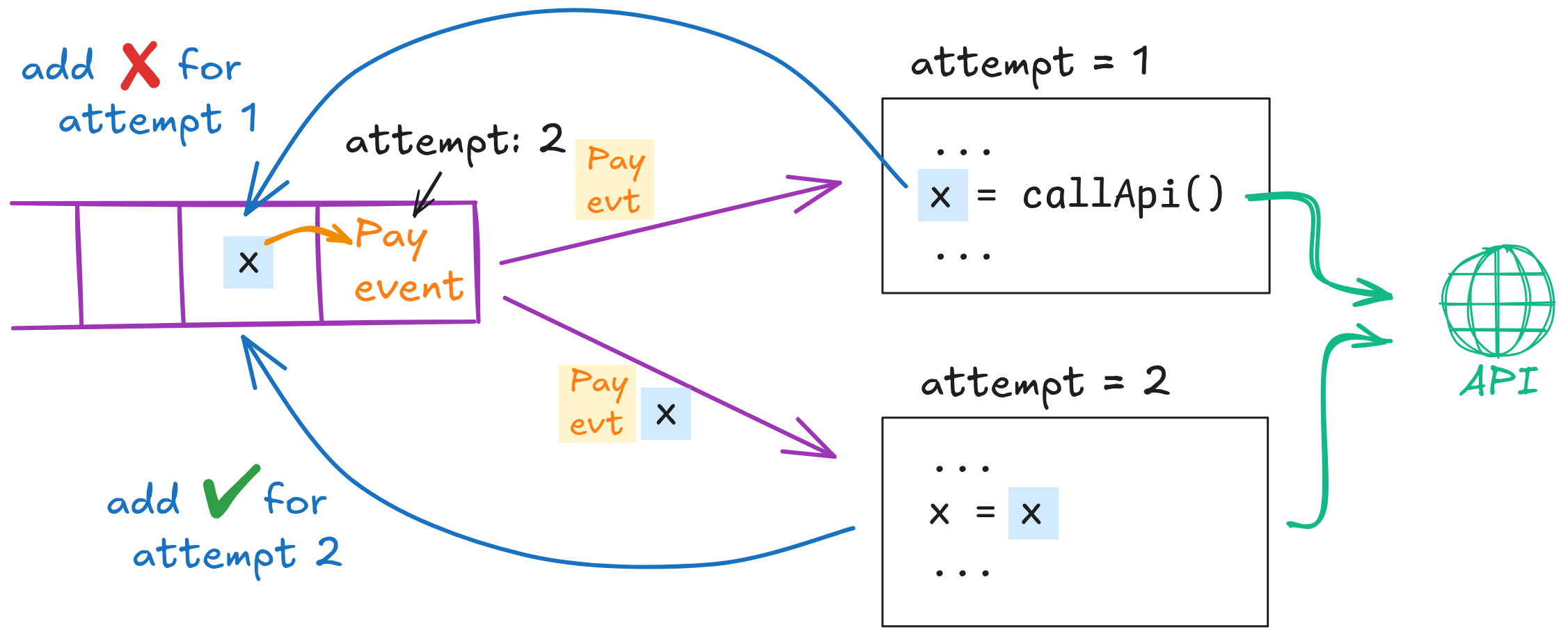

Now let’s assume that all these systems (queues, DBs, locks, ...) operate off the same log - for the sake of this thought experiment - the log of the message queue that delivers the PaymentEvent to the processPayment handler (the upstream log).

Every time our processPayment handler wants to change some state of another system, it writes a record to the upstream log. That new record is linked to the original PaymentEvent. Whenever the queue decides to re-deliver the PaymentEvent again (e.g., under a timeout or an assumed failure), it also attaches all linked log entries (the journal).

Now we can adjust lines 9,10,11 (the call to the fraud-detector API and storing the result) to write the result of the API call to the upstream log. When the handler is retried after a potential failure, it automatically sees whether the result was written before. This is not just efficient, but we no longer store completed steps in a shared DB where it is easy to have it accidentally picked up in unexpected ways (see this article for how this can be a severe security and integrity loophole).

This becomes particularly useful, if we require a conditional append to add an entry to the log: We can only append that entry, if no newer retry was triggered. That is easy for a queue to track (it knows whether it sent the PaymentEvent out again) and our processPayment handler would quit if the conditional append failed, knowing that another retry attempt has taken over.

Now, concurrently executing retries (if the queue incorrectly assumes a handler failed and re-sent the event) can no longer corrupt the step history. This implementation gives us pretty strong workflow-style execution guarantees for our code!

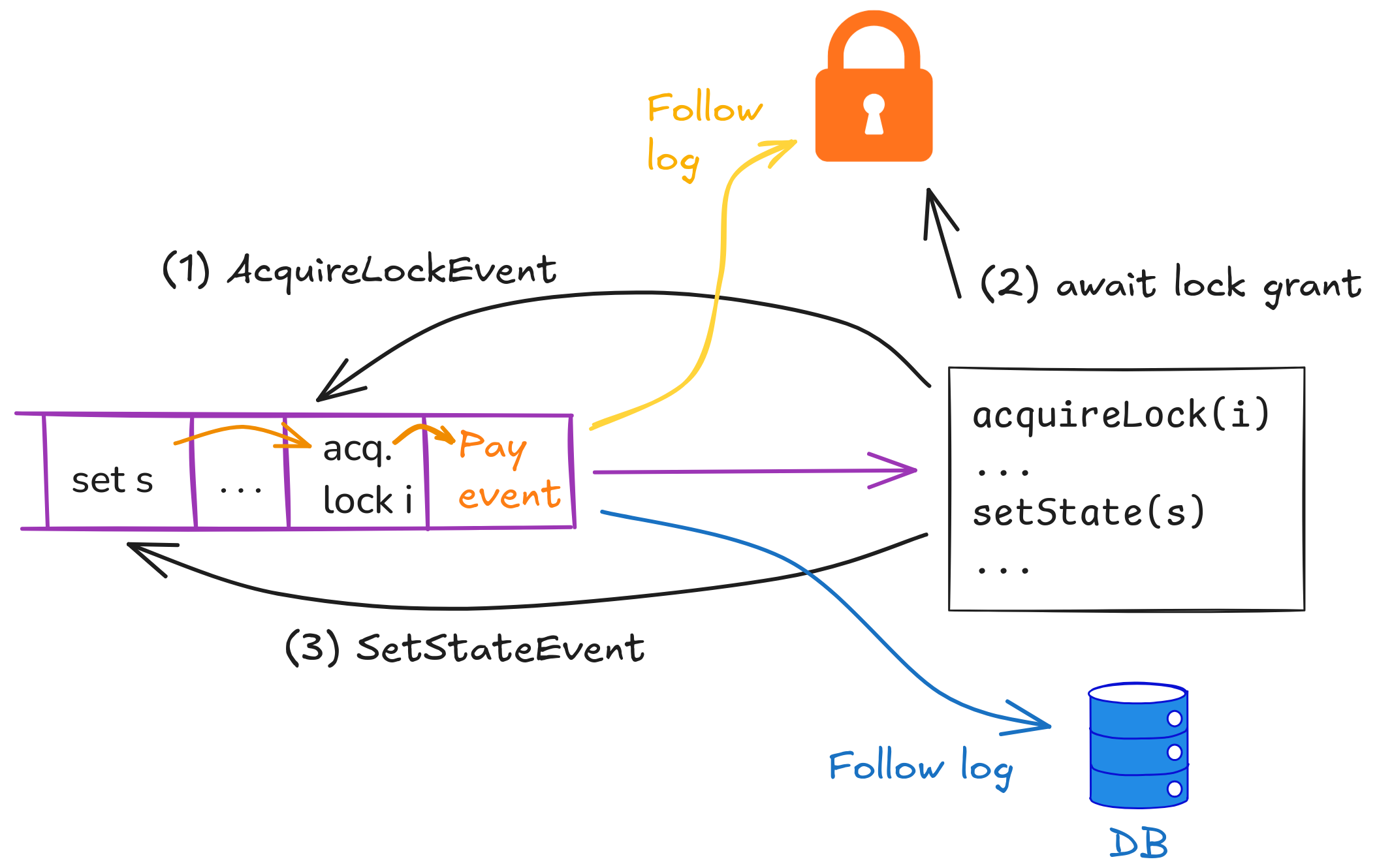

To make locking (line 2) and state update (line 20) work reliably, the processPayment handler writes the relevant events (acquire lock, release lock, update state) to the upstream log as well. After writing the acquire lock event, the handler waits until the lock service grants the lock.

The lock service and the database now follow the upstream log as if it was their own write-ahead log. The database can simply apply the update when it reads the event, the locking service of course only grants the lock when available (might have to wait to encounter the previous holder’s release lock event).

Somewhat surprisingly, this pretty much eliminates all problems and corner cases we had with locks and state before: Lock acquisition and release through the upstream log and handler’s journal means we reliably keep the lock across retries. Having the update event conditionally appended to the same event journal as the lock event replaces the need for the lock's fencing token - plus, we can be sure that we apply the update once and only once.

So, once we implement our logic like this, EVERYTHING JUST WORKS.

We can inject all sorts of failures, stalls, network partitions. As long as the log is correctly implemented, the program will always remain correct. And all that the processPayment handler needs to do is (1) trigger actions as conditional-log-appends and (2) skip over actions whose log entries are already attached to the PaymentEvent. This is super easy to implement in a library, because it doesn’t require any form of distributed coordination.

If everything's in one log, there's nothing to coordinate

We haven’t added a new distributed system primitive; in fact we’ve removed several. The benefits come from avoiding the need for coordination.

Before we started using the same log, the state was spread across systems: The status of the operation, whether a lock is held, who held it, what value a branch was based on. Because each system maintains their state as if it was independent, the different parts of the state can get out-of-sync and be altered in unexpected ways (e.g., through a race condition or zombie process). It’s hard to implement robust logic and guarantee strong invariants that way.

Having a single place (the one log) that forces a linear history of events as the ground truth and owns the decision of who can add to that ground truth, means we don’t have to coordinate much any more.

Coordination avoidance is one of the few silver bullets in distributed systems - a way to reduce complexity, rather than shift it. For example, guarding our second code snippet with a ZooKeeper lock only shifted complexity. It reduced the code’s need to worry about concurrency, but introduced issues around lost locks and cleanup of persistent locks. In contrast, the approach to unify the different states in one log actually reduced work, which resulted in higher efficiency, fewer corner cases, and easier operations.

I know what you’re thinking: That’s a nice thought experiment, but my queue/log doesn’t work like that, my database doesn’t follow some other log, and isn’t this breaking all rules for separation of concerns?

Adopting this idea in practice

This idea can serve as a conceptual blue-print for an architecture based on a log (e.g., Kafka) - a bit like “Turning the Database Inside Out” (maybe we should call this “Turning the Microservice Inside Out?”). In practice, today’s log implementations miss efficient built-in ways to track retries, make conditional-appends, link events into a journal, and would leave that to the application developer to implement.

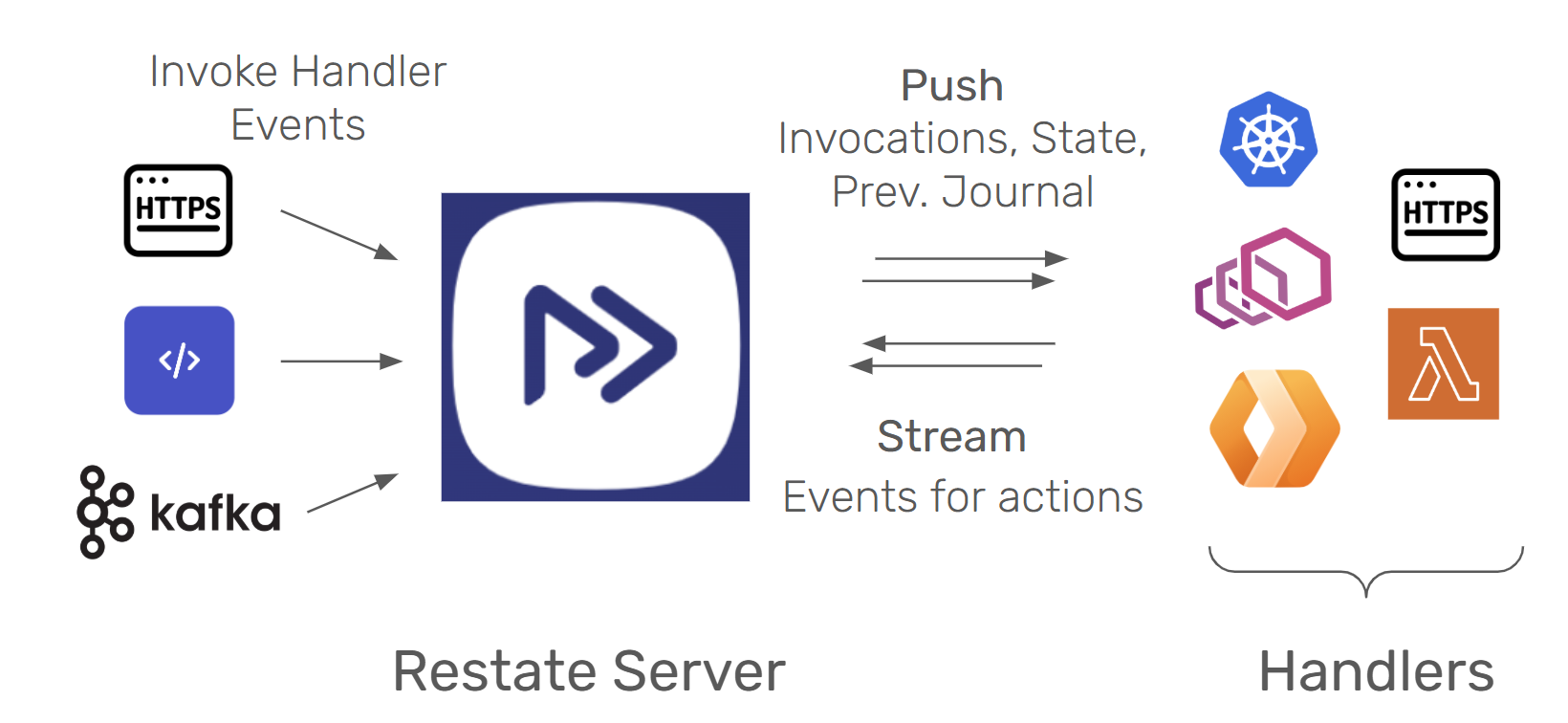

Restate is an implementation of this idea. Restate Server is the broker that owns the upstream log and push-invokes the handlers with events (e.g., similar to AWS SNS and Event Bridge), ensuring reliable retries after crashes. Every event gets the latest execution journal (set of linked events) attached, just as described in the thought experiment above. Restate uses bi-directional streaming protocols (e.g., HTTP/2) to invoke the event handlers and send journal events and acknowledgements back and forth.

The server issues a unique epoch to every invocation and retry, which the SDK attaches to every journal event that it sends, allowing the server to reject events from subsumed handler executions (the conditional append).

The code snippet shows the example in Restate’s API (here TypeScript, but Java, Kotlin, Python, Go, and Rust are supported as well). The code does not explicitly append log events, but rather uses an SDK for actions, and the SDK interacts with the log.

To persist intermediate steps (line 8), handlers use the SDK (ctx.run), which sends the event to the log and awaits the ack of the conditional append to the event’s execution journal. On retries, the SDK checks the journal whether the step’s event already exists and restores the result from there directly.

Messages to other handlers are transported with exactly-once semantics (line 16). Message and RPC events are both added to the journal and routed to the destination handler. Similar to ctx.run, the journal deduplicates the message-sending steps. Because messages result in a single durable invocation (sequence of retries that share a journal), you can easily build end-to-end exactly-once semantics on top of this.

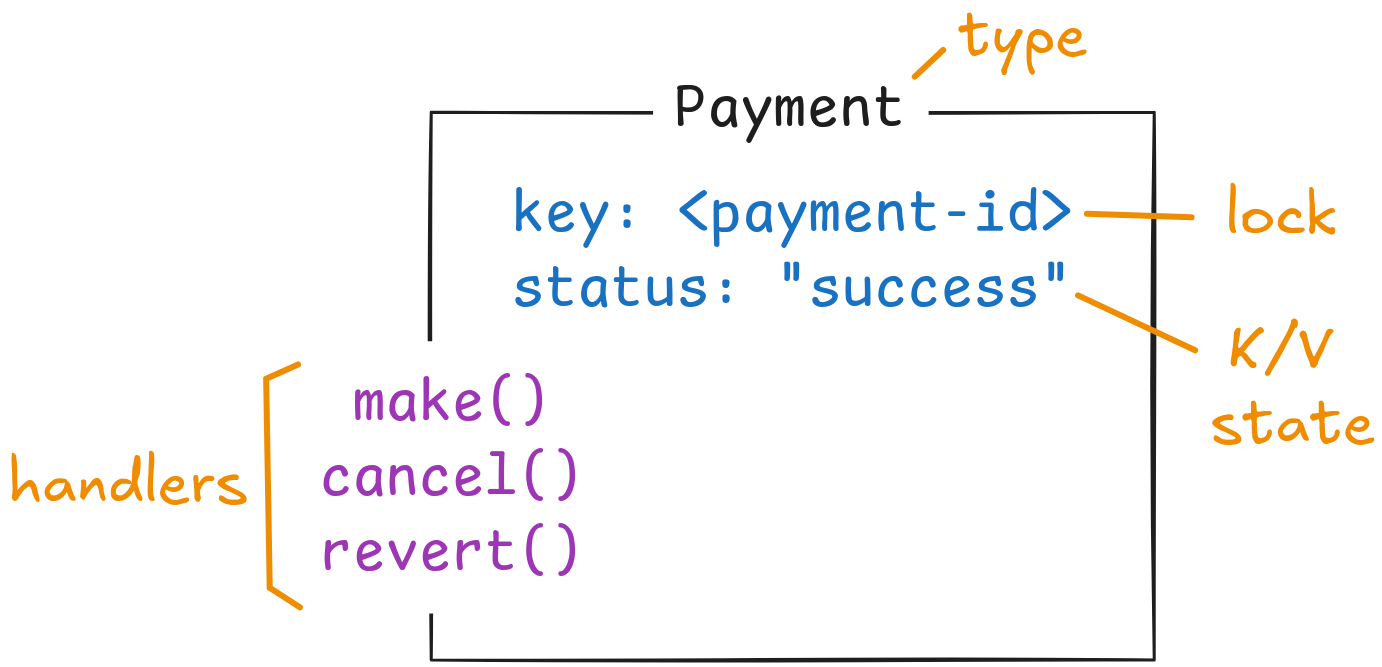

Restate supports handlers that lock a key when executing (and hold the lock across retries). Those handlers can read and update state that is scoped to that key. They are implemented similarly to the thought experiment: The lock and state update events are added to the journal and additionally processed by an embedded lock service and K/V store, making locks and state virtually incorruptible through partial failures, race conditions, zombie processes, etc.

These stateful handlers can be grouped together to share state. Restate calls that a Virtual Object, because the handlers are like methods with access to the object instance’s state. The state is infinitely retained in the K/V store, even when the log events eventually get garbage collected.

There are more building blocks in Restate, including persistent Futures/Promises, timers, or idempotency-keys . They all build on the same concept: Events routed through the same log, stored in the journal, and processed into a database or scheduler.

Applications often aim to create the behavior of stateful, reliable, and resumable execution for their critical functions. The single-log approach provides that with a single dependency and without coordination across queues, DBs, locks, and schedulers. Restate implements that pattern.

Blast radius and separation of concerns

It would not make sense to use a single log for every operation in a distributed multi-service architecture. While it could give interesting properties, this would couple services too tightly, create a single giant blast radius, and void many benefits of service-oriented designs.

The sweet-spot we target with Restate’s implementation of this idea, is to drive all state that is strictly scoped to a handler or service through the log, plus transport of messages between services. The result is a coupling and blast radius similar to any event-driven service: If the upstream queue/log is down, the service cannot be invoked.

State in a database or in the log?

We assume that Restate is not going to replace general purpose databases. Shared databases should and will remain a part of the infrastructure, and continue to do what they are great at.

The K/V state built on the log is a great fit for state machines (like the status of a payment), temporary state when joining/aggregating events and signals, or really any state that is purely updated through the event-driven handlers and scoped around a key (though a key may be something broader, like an aggregate root in Domain Driven Design).

It also gives you the building blocks for a highly robust and consistent core state. You can even use that to build overlays over other stores, track metadata like versions for entries in databases, or build data structures like semaphores. Here is an example of how to use this to make exactly-once updates to databases from handlers.

What’s next?

Today, Restate runs on a single node - similar to a Postgres database server. In the next few weeks, we will release a first version of Distributed Restate, supporting replication, scale out deployments, working with object store snapshots - stay tuned for more exciting updates during that release.

With the release, we will publish Part 2 of this article, which is looking at the design of the broker that maintains that log, drives the execution, retries, and implements the extensible logic to use the log for communication, locking, journaling, state, signals, scheduling, etc. As you might expect, if the core abstraction is a log, that system is a specific type of event-driven architecture.

In Part 3 of this series, we look at the implementation of the log that backs everything. Why not just use Kafka? Or just use Postgres? In this case, we opted to develop a new type of log - something that generally one shouldn’t do, but once in a while, there is actually a good case for it. We believe that this is one of those cases, and will discuss the details of the log design, what makes it unique, and what it can do that’s hard to do with any existing implementation.

If you want to try this pattern out for yourself and see and feel this idea in action, Restate is open source. Get started with the quickstart guide, star the GitHub project, and join the community on Discord or Slack. Be the first to know about new releases and technical posts by following us on X, LinkedIn, Bluesky, or subscribing to email updates.